The Ultimate Guide to Stovetop Tea Brewing: Become a Pro at Gathering Around the Stove for Tea

As Frost’s Descent passes, chill quietly spreads across the land. At this moment, nothing is more comforting than lighting a stove, gathering with a small group of friends, and brewing a pot of warm tea while chatting away the afternoon in tranquility.

This popular "gathering around the stove to brew tea" trend is often labeled as "new" or "viral," but it’s far from a modern invention. It originates from the "fire pit roasted tea" deeply rooted in the traditions of Yunnan’s ethnic minorities. In Yunnan, the fire pit is the heart of the home and a natural place for brewing tea: put an appropriate amount of tea leaves into a clay pot, roast over the fire until fragrant, then pour in boiling water. This is an ancient tea-drinking method that Chinese people have preserved for thousands of years.

The time-honored practice of boiling tea dates back to the "boiled tea soup" of the Spring and Autumn Period. Tea branches and buds were boiled with water in containers, and the bitter taste earned it the name "bitter tea." By the Wei, Jin, Southern and Northern Dynasties, it was popular to add condiments like green onions, ginger, jujubes, dogwood, and mint to balance the tea’s inherent bitterness. The Book of Jin records, "People in Wu pick tea and boil it, calling it tea porridge."

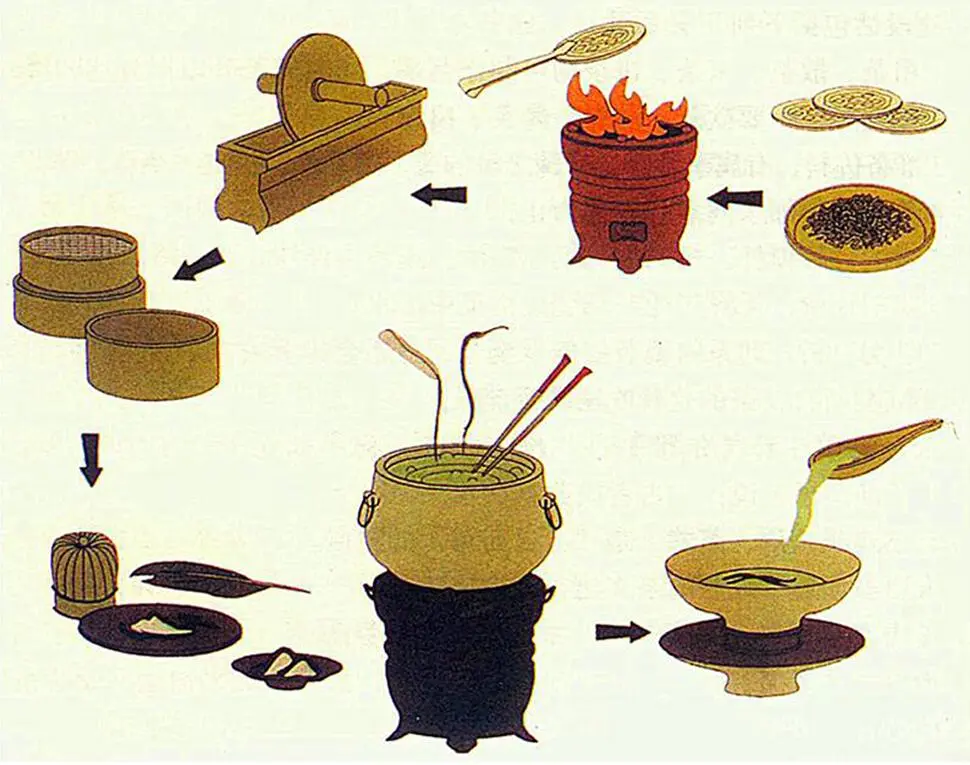

In the Tang Dynasty, Lu Yu, the Sage of Tea who pursued the true flavor of tea, created the "tea decoction method." Abandoning the complicated condiments of the Wei and Jin dynasties, he roasted tea cakes, ground them into powder, boiled with water, and seasoned only with a pinch of salt to achieve a pure, mellow tea soup.

Although "whisked tea" dominated the Song Dynasty, the custom of boiling tea never faded. The poet Lu You wrote, "Clear sweet snow water fills the well spring; I carry my tea stove to brew," savoring the tea’s purity through self-brewing. Du Lei’s line, "On a cold night, when guests arrive, tea replaces wine; the bamboo stove’s water boils as the fire glows red," vividly depicts the warmth and elegance of serving tea to guests. Today, this millennia-old boiling method has evolved into a simple form of simmering tea leaves with pure water.

It may seem simpler than regular steeping, but it hides many secrets: "Which teas are best for boiling?" "Should I use cold or hot water?" "What material teapot works best?" Today, we’ll cover everything thoroughly!

I.Choose the Right Tea: Not All Teas Are Equally Boil-Resistant

Many people wonder why some teas become more fragrant after prolonged high-temperature boiling, while others turn unbearably bitter. The answer lies in the tea’s leaf tenderness, fermentation level, and storage time.

Leaf tenderness determines boil resistance. Teas with tender buds and leaves—such as green tea, yellow tea, high-grade white tea (Silver Needle, White Peony), and premium black tea (Jinjunmei, Dianhong Golden Needle)—release nutrients quickly. Boiling them tends to bring out bitterness, making them unsuitable for this method.

In terms of fermentation: oolong tea (semi-fermented), black tea (fully fermented), and dark tea (post-fermented) are all ideal for autumn and winter boiling. Unfermented green tea and lightly fermented yellow tea should not be boiled, while lightly fermented white tea requires caution.

When it comes to storage: white tea improves with age, and well-stored old white tea is perfect for boiling. The tea community’s saying "Old white tea is meant to be boiled" highlights its compatibility with this method. White tea is available as loose-leaf or compressed cakes. Loose-leaf tea has a loose structure and slow transformation, so it’s better to boil after 5+ years of storage. Compressed white tea cakes transform faster and can be tried after 3+ years.

For Pu-erh and Liubao tea, classification depends on whether they undergo "wet piling." For younger teas, raw Pu-erh and traditionally processed Liubao tea are less boil-resistant than ripe Pu-erh (which undergoes wet piling) and modern-processed Liubao tea.

To help you choose more intuitively, our team conducted detailed boiling tests on different teas. The final boil-resistance ranking is: green tea (unfermented) < yellow tea (lightly fermented) < black tea (fully fermented) < oolong tea (semi-fermented, aged) < dark tea (post-fermented, ripe Pu-erh/wet-piled Liubao) < old white tea (lightly fermented, loose-leaf >5 years/compressed >3 years).

II.Choose the Right Water: Cold vs. Hot Water Yield Different Flavors

Veteran tea drinkers know boiling tea falls into two camps: "cold water boiling" and "hot water boiling." The former involves adding tea leaves directly to cold water and boiling them together. The latter requires boiling water first, then adding tea leaves to simmer before serving.

The key difference lies in the contact time between tea and water, resulting in distinct flavors. We tested the same aged Qimen An tea (tea-to-water ratio 1:150) for both methods:

1. Cold Water Boiling

Tea leaves contact water continuously as the temperature rises. Over time, nutrients like tea polyphenols and caffeine are released slowly and steadily, creating a "strong, intense" tea soup. However, this intensity comes with a downside: the soup feels rich on the palate but is overshadowed by noticeable bitterness, lacking smoothness.

2. Hot Water Boiling

Adding tea leaves to fully boiled water instantly awakens the aroma. Soon, you’ll smell the ancient indocalamus fragrance of aged Qimen An tea—rich, long-lasting, and paired with a quickly darkening soup. The taste is sweet, pure, and smooth, with significantly reduced bitterness.

This is because the short contact time between tea and hot water prevents over-extraction of tea polyphenols and caffeine, balancing aroma and taste for better drinkability. In short, cold water boiling’s "slow release and long accumulation" lets bitter compounds dominate—full flavor but overly bitter. Hot water boiling’s "quick activation and clever balance" highlights strengths and avoids weaknesses, preserving drinkability.

Not all teas are suitable for direct boiling. For compressed tea, aged tea, and post-fermented dark tea, it’s advisable to quickly "awaken the tea" with hot water first. This removes off-flavors and refines the taste. You can also try the "steep first, then boil" method: steep 3-5 times in a gaiwan or purple clay teapot, then transfer to a stovetop kettle to simmer. This results in a milder soup, avoiding excessive bitterness from direct prolonged boiling.

III.Choose the Right Teapot: Glass vs. Clay Teapots Each Have Advantages

There’s a saying in the tea world: "The vessel is the father of tea." The same tea brewed in a gaiwan vs. a purple clay teapot yields different flavors. Similarly, the material of a stovetop teapot shapes the tea’s aroma and taste. Glass and clay teapots are the most popular options, each with unique benefits.

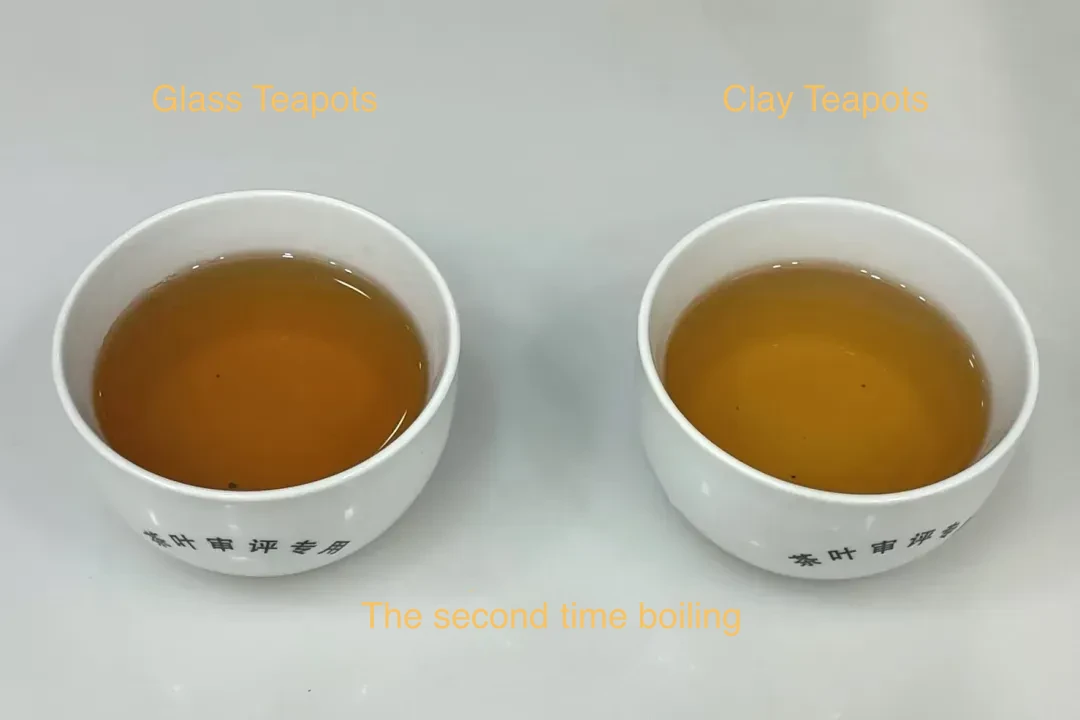

In our previous comparison test of 2016 aged Shoumei tea cakes (tea-to-water ratio 1:200, 400w power, tea added after boiling), the two teapot types produced drastically different results:

1.Glass Teapots

Made of borosilicate glass, they offer high heat resistance, hardness, and chemical stability, leaving water quality unaffected. However, poor insulation keeps the tea boiling continuously, causing compressed Shoumei leaves to unfurl quickly. The soup darkens fast, and aroma spreads instantly.

After 7 minutes of boiling (the same duration for both teapots), the glass teapot’s tea had a zongzi leaf fragrance, but the aroma floated on the surface rather than integrating with the soup, which tasted slightly watery. Continuous boiling also accelerated the release of caffeine and tea polyphenols, making the flavor stronger. For a second brew without refilling, the soup turned darker yellow with a rich jujube and zongzi leaf aroma, but still lacked integrated flavor.

Glass teapots excel in soup concentration and heat retention stability. They suit those who dislike waiting, but shorter boiling times are recommended to avoid increased bitterness.

2.Clay Teapots

Crafted from natural mineral clay, often mixed with fine barley stone powder and Australian spodumene, they are thick, airtight, and excellent at heat insulation and retention. Adding boiling water to tea leaves was calmer compared to glass teapots.

The tea in the clay teapot took 7 minutes to fully boil, yielding a bright pale yellow soup with a lingering floral aroma. Most impressively, the aroma integrated with the soup, offering a sweet, smooth, and layered taste. For the second brew, the soup turned orange-yellow, remaining sweet and full-bodied with preserved floral notes and developed aged fragrance. However, the flavor slightly diminished as the soup cooled, unlike the glass teapot’s stable taste.

Clay teapots’ "slow boiling" suits those pursuing layered flavors. Their good airtightness absorbs impurities, softens water, and enhances smoothness. Excellent heat retention helps "awaken tea flavor and boost aroma."

IV.Key Details and Safety Tips for Boiling Tea

Beyond choosing tea, water, and teapots, the essence of boiling tea lies in small details. Modern Chinese-style stove-side tea often uses charcoal, and selecting the right charcoal matters!

Lu Yu wrote in The Classic of Tea·Chapter Five: Boiling, "For fire, use charcoal; next, hard firewood." The Sage of Tea believed pure, impurity-free charcoal and hard dried woods like mulberry, locust, paulownia, and oak burn steadily without releasing odd odors, preserving the tea’s true flavor.

Chaoshan Gongfu tea also pursues excellence in charcoal. Its "Four Treasures of the Tea Room" include the "Yushu Wei" (kettle), "Chaoshan Stove," "Mengchen Pot," and "Ruochen Cup." The Chaoshan red clay stove uses olive pit charcoal specifically for boiling water. Hard olive pit charcoal burns densely, evenly, and long, slowly raising water temperature to produce soft, lively water. Brewing Phoenix Dancong with this water releases more aromatic layers.

The warmth of charcoal-brewed tea is charming, but the risk of carbon monoxide poisoning must be taken seriously. When using charcoal stoves indoors, ensure good ventilation to prevent carbon monoxide buildup from incomplete combustion.

With technological advancements, electric stoves—no fire required, convenient, and hassle-free—have become a popular choice for indoor tea boiling. Two key points to note:

- Do not overfill the kettle (water level should not exceed 80%) to prevent boiling water from spilling into the stove, causing short circuits or electric leakage.

- Match the stove’s power to the teapot material. Glass and clay teapots suit low to medium power for slow boiling, avoiding cracking from sudden high heat.

The warmth of autumn and winter lies in a pot of steaming tea. Every careful step—choosing tea, water, teapots, and charcoal, plus prioritizing safety—aims to bring out the best flavor.

Next time, try preparing tea, selecting a teapot, lighting charcoal, boiling water, adding tea, and savoring according to this guide. What tea do you prefer boiling? Feel free to share your private stove-side tea collection in the comments!

Leave your comment

Note: HTML is not translated!